Passport to Hell, anyone?

In an attempt to revitalize my interest in an artier brand of cinema (I'm currently working on a project about white women whose babies are abducted - hence a plethora of Jodie Foster and Julianne Moore movie, Lifetime...), I picked up a couple foreign Queer films that I have been hearing both praise and condemnation of for some time. Figuring it was time to have a say so myself, sat down over the course of two evenings with the Portuguese film, O Fantasma and the post-Punk, Germanic Prinz In Hölleland(Prince in Hell).

Film Comment sings to the high heavens about the films of João Pedro Rodrigues, whose most recent film, Odette (or, if you're the American distributer, Strand, and know you can only market foreign films by catering to the flesh hungry Zombi... errr homosexuals, Two Drifters - replete with image of 2 boys kissing, when the film is in fact about the eponymous girl). O Fantasma was a film I wanted very much to like. Bare bones plot, appreciation of minimal cinematic devices. Yet when the credits flashed upon the screen, the perplexing discernment which makes a film like Claire Denis' L'Intrus so rewarding ultimately cripples O Fantasma

Film Comment sings to the high heavens about the films of João Pedro Rodrigues, whose most recent film, Odette (or, if you're the American distributer, Strand, and know you can only market foreign films by catering to the flesh hungry Zombi... errr homosexuals, Two Drifters - replete with image of 2 boys kissing, when the film is in fact about the eponymous girl). O Fantasma was a film I wanted very much to like. Bare bones plot, appreciation of minimal cinematic devices. Yet when the credits flashed upon the screen, the perplexing discernment which makes a film like Claire Denis' L'Intrus so rewarding ultimately cripples O Fantasma

In our hour and a half in the narrative's clutches, we are treated to the slow, psycho-sexual downfall of our protagonist, Sergio. A pervert, through and through with a consistence which could set him aside some of cinemas cherished perverts (Karlhienz Böhm from Peeping Tom comes to mind) were it not for his hustler brooding and flawless beauty. I love snogging just as much as the next, but I yearn for the day in which someone makes a sexually charged gay film in which the protagonist is not such a looker (and no, Big Eden doesn't count - there, his lack of appeal was of greater point than his coincidental joe-ness). Auto-erotic asphyxiation, pissing, licking, sucking, fucking, being fucked, trespassing, biting, fetishizing found skivvies, gloves, garbage ensues but to an obtuse end which involves a less than effective narrative shift which leaves one wanting for the seldom usage of the effective figure in [Safe], whose full body suit shielded him from the outside world, yet also from us, as his presentation was so spare in the movie that his awkward trek about the outskirts of the compound was ghosted upon our retinas. Here, our sexually enclosed figure eats garbage and abuses animals, but to no true great purpose. This is no Jodorowski - whose alternate worlds maintained a grizzly consistency. It is merely odd and uncompelling.

In our hour and a half in the narrative's clutches, we are treated to the slow, psycho-sexual downfall of our protagonist, Sergio. A pervert, through and through with a consistence which could set him aside some of cinemas cherished perverts (Karlhienz Böhm from Peeping Tom comes to mind) were it not for his hustler brooding and flawless beauty. I love snogging just as much as the next, but I yearn for the day in which someone makes a sexually charged gay film in which the protagonist is not such a looker (and no, Big Eden doesn't count - there, his lack of appeal was of greater point than his coincidental joe-ness). Auto-erotic asphyxiation, pissing, licking, sucking, fucking, being fucked, trespassing, biting, fetishizing found skivvies, gloves, garbage ensues but to an obtuse end which involves a less than effective narrative shift which leaves one wanting for the seldom usage of the effective figure in [Safe], whose full body suit shielded him from the outside world, yet also from us, as his presentation was so spare in the movie that his awkward trek about the outskirts of the compound was ghosted upon our retinas. Here, our sexually enclosed figure eats garbage and abuses animals, but to no true great purpose. This is no Jodorowski - whose alternate worlds maintained a grizzly consistency. It is merely odd and uncompelling.

There is, on the other hand, a peculiar sweetness to Michael Stock's Prinz in Holleland(Prince in Hell). Like a slightly less self-absorbed Bruce LaBruce (though still starring and directing) Stock's film functions best as a social document. Like Jarman's Jubilee, the film reminds of a more hopeful moment in time. The nineties were not alien to alienation - not in the slightest - but their brand of disenfranchised was far more active, utopian. Here, we have a caravan of misfits (including a jester who would seem to have just blown in from the Porno adaptation of Rudolf's Island of Misfit Toys) who quarrel about drug use and politics. There's a child about who imbues the film with a wide-eyed optimism echoed in the eyes of our polysexual degenerates. Of course, nothing good can ultimately come of this, but there are some surprisingly endearing moments along the way.

There is, on the other hand, a peculiar sweetness to Michael Stock's Prinz in Holleland(Prince in Hell). Like a slightly less self-absorbed Bruce LaBruce (though still starring and directing) Stock's film functions best as a social document. Like Jarman's Jubilee, the film reminds of a more hopeful moment in time. The nineties were not alien to alienation - not in the slightest - but their brand of disenfranchised was far more active, utopian. Here, we have a caravan of misfits (including a jester who would seem to have just blown in from the Porno adaptation of Rudolf's Island of Misfit Toys) who quarrel about drug use and politics. There's a child about who imbues the film with a wide-eyed optimism echoed in the eyes of our polysexual degenerates. Of course, nothing good can ultimately come of this, but there are some surprisingly endearing moments along the way.

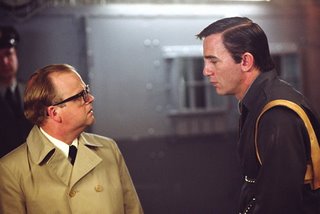

Keep your eyes peeled for Harry Baer, the Fassbinder regular. Though, if you're like me and found him devastatingly sexy in whatever incarnation Rainer through his way, you are bound to have some dreams shattered. His, if I may make a rather abstract analogy, is perhaps a telling appearance - his inclusion in this film, at the wane of an international German cinema is symbolically potent. As the washed-up pervy dealer Ingolf, he can barely muster the energy to slip on more than a bathrobe. This is how the doomed function, and sadly, an international German cinema is still nowhere nearer.

Keep your eyes peeled for Harry Baer, the Fassbinder regular. Though, if you're like me and found him devastatingly sexy in whatever incarnation Rainer through his way, you are bound to have some dreams shattered. His, if I may make a rather abstract analogy, is perhaps a telling appearance - his inclusion in this film, at the wane of an international German cinema is symbolically potent. As the washed-up pervy dealer Ingolf, he can barely muster the energy to slip on more than a bathrobe. This is how the doomed function, and sadly, an international German cinema is still nowhere nearer.