Bananarama

Last night I attended FilmForum's Warhol weekend screening of some assorted screen tests and Harlot, a 66 minute sound film (Warhol's first - it is rather worthy of note). The film stars Jack Smith's superstar Mario Montez, attempting to assure a niche for herself in an underground on the verge of a great transition. Working with Smith in the early 60's - who, in turn, found his initial labors as actor in the works of Ken Jacobs and Ron Rice - Montez's performances were unconditional labors of love. With the arrival of Warhol, the successful fashion illustrator cum pop artist, a sudden economy was given to an otherwise impoverished medium. Harlot is a fantastically poignant exemplar of this divide. Montez, who is accustomed to Smith's jittery and oscillating camera movement, first imbues a figure of performative prowess, yet as the stationary camera glares on, loses more and more confidence.

Last night I attended FilmForum's Warhol weekend screening of some assorted screen tests and Harlot, a 66 minute sound film (Warhol's first - it is rather worthy of note). The film stars Jack Smith's superstar Mario Montez, attempting to assure a niche for herself in an underground on the verge of a great transition. Working with Smith in the early 60's - who, in turn, found his initial labors as actor in the works of Ken Jacobs and Ron Rice - Montez's performances were unconditional labors of love. With the arrival of Warhol, the successful fashion illustrator cum pop artist, a sudden economy was given to an otherwise impoverished medium. Harlot is a fantastically poignant exemplar of this divide. Montez, who is accustomed to Smith's jittery and oscillating camera movement, first imbues a figure of performative prowess, yet as the stationary camera glares on, loses more and more confidence.

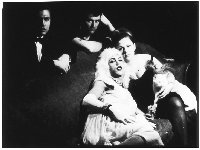

Warhol regular Gerrard Malanga is seated behind her, arms positioned over the edge for the couch. He is unusually well coiffed. The performative struggle for power teetering between the two, with Malanga holding little but sexual control over Montez. But then, when is sexual control ever little? Seated beside Montez is Carol Koshinkie, also dressed to the nines with a beer can in one hand and a large white cat in her lap. She sit before the devastating cruiser Philip Fagan - Warhol's assistant/boyfriend, at the time - both figures, in the film's most fantastically dynamic formal device, seldom break the courting stare they shoot directly into the camera(or subsequently at you, dear viewer). In the minimalist formalities of Warholian cinema, these stares create a remarkable dramatic tension. Watching Fagan watching me turned me on with its delicate balance of exhibitionist-voyeuristic way. Your eyes dart from the exploited Montez, as she erotically downs countless bananas (taking a sad departure from her gender-free, "creature" status in Smith's cinema), to the cruising onlookers, to the rather clueless Malanga. Though limited, Warhol's framing is fantastically diverse in its composure and even when Montez begins to lose steam (and to a lesser extent, the film along with it) you never find yourself resting on one image for too long.

Harlot's endlessly amusing soundtrack features great spoken word performances by Smith collaborator Ronald Tavel and Factory documentarian/mole person, Billy Name. Tavel, a poet who would later go on to pen numerous scripts for Warhol, engages our interest with his unusually quick plays on words. A marriage of convenience becomes "a cat of convenience."

"What do you call a person who eats only fruit?"

"A liar!"

Ultimately, however, Warhol's cold glare on the lovable Montez is sadly cruel for anyone who knows her work from Smith's films. Unsure of what to do around the static shot's 50 minute mark, Montez begins to stimulate herself with one of the film's great many bananas. First tracing her legs languidly, the fruit slowly disappears into her skirt. On most this could be quite thrilling or rebellious, but Montez, in all of her naive innocence, merely looks lost.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home