Busted

Certain films become phenomena long before a moment of their celluloid is shed onto the screen. The magnitude of these expectations may work in both ways. Typically, when it comes to works of a more independent variety, it results in a crippling span of disappointment – those grandiose, imagined ideals which the viewer had nurtured can seldom find any sort of fulfilling release in the very “real” events on screen. The other side to this is that ardent base of admirers who know, full well, that they will be enjoying that which they are about to see as, like a sexual climax, the partaking is the desired end for this long quest. The trials and travails, which director John Cameron Mitchell endured to see the actualization of his sophomore feature, are already quite infamous. Of course, the impeccable status of his debut work only helped. The phenomenon which became Hedwig and the Angry Inch was steeped in its cabaret origins, its quite cultish subject matter and fertilized by the buzz that enveloped the film after its release. It caught on. It was not insane at first. Now there are weekly midnight parties, á la Rocky Horror. John Cameron Mitchell’s follow-up has been one rocky road from the get go. I won’t go into that here. Let’s just say it took him a while and, with baited breath, an avid crew of the curious sat poised to see how his next offering would hold up. Would he merely be Hedwig?

I wept during Shortbus. (Isn’t that illegal for a film critic to admit?) It’s the kind of film you hear of in recollections. It’s something you might stumble across as a distorted still in Vogel’s ‘Film as Subversive Art.’ Kind of. Most of those works – Vienna Actionists and the like come from a darker place. Ono’s in there, and I would certainly cite her as an impetus for this film. It’s honest and heart-felt – all without the guiding hand of direct (or cheap, perhaps) sentimentality, directing your every emotive sway. It recounts the story of a handful of very common people. They are average. Some critics have had the poor taste to write that these are people you would not particularly care to watch having sex. I think that’s a tad naff. I think that stems more from a need for the critic to divorce his/her titillation factor from the critical job at hand. Ain’t possible. Sorry. True, none of these figures is Ashton Kutcher, but in a great many respects they are all the more compelling for not being so. I would much rather watch Sook-Yin Lee’s Sofia masturbate on a park bench than watch Kutcher in a similar sexual act. And I am a homosexual.

I wept during Shortbus. (Isn’t that illegal for a film critic to admit?) It’s the kind of film you hear of in recollections. It’s something you might stumble across as a distorted still in Vogel’s ‘Film as Subversive Art.’ Kind of. Most of those works – Vienna Actionists and the like come from a darker place. Ono’s in there, and I would certainly cite her as an impetus for this film. It’s honest and heart-felt – all without the guiding hand of direct (or cheap, perhaps) sentimentality, directing your every emotive sway. It recounts the story of a handful of very common people. They are average. Some critics have had the poor taste to write that these are people you would not particularly care to watch having sex. I think that’s a tad naff. I think that stems more from a need for the critic to divorce his/her titillation factor from the critical job at hand. Ain’t possible. Sorry. True, none of these figures is Ashton Kutcher, but in a great many respects they are all the more compelling for not being so. I would much rather watch Sook-Yin Lee’s Sofia masturbate on a park bench than watch Kutcher in a similar sexual act. And I am a homosexual.

It has also been written repeatedly that the “real” sex which the film does depict is not the clinically pornographied version of coitus that someone like Catherine Breillat (Romance, Anatomy of Hell) has made an art form out of, nor is it the performative sex which made the most of Michael Winterbottom’s insipid Nine Songs, but in fact brief and unsensational sequences which clock in at the same length an R rated film might devote to them. They are just scenes to a whole, nowhere near as important as the press would demand. (Question: When will Americans get over this abject fear of all things direct? We are flooded with sex and yet this film is controversial? Have the viewers who will see Shortbus not been to a foreign film in the past 10 years?) And it is unfortunate, as that taboo which Mitchell set out to brake might prove to be the fatal error, attendance wise, in this must see magnificent film. Of course, it would do the film itself a great disservice to simulate what is quite fundamentally its essence. But fucking is never really just fucking, and in when the frigid Sofia finally enters the “back room” of the film’s eponymous club, you get it. You see fucking, true. You also catch wind of promise, nurturing, fear, isolation, devastation, and transcendence – all of this in a swirling, slurping pool of bodies. The impeccable Justin Bond (here proving his legitimacy to me, after never truly being hooked by his Kiki and Herb material) says to Sofia (in the much quoted line) “It’s like the sixties only with less hope.” And that line could completely sum up Shortbus were it not for Mitchell’s signature fairytale styling which renders the film a jubilant concoction of desolation and celebration.

It has also been written repeatedly that the “real” sex which the film does depict is not the clinically pornographied version of coitus that someone like Catherine Breillat (Romance, Anatomy of Hell) has made an art form out of, nor is it the performative sex which made the most of Michael Winterbottom’s insipid Nine Songs, but in fact brief and unsensational sequences which clock in at the same length an R rated film might devote to them. They are just scenes to a whole, nowhere near as important as the press would demand. (Question: When will Americans get over this abject fear of all things direct? We are flooded with sex and yet this film is controversial? Have the viewers who will see Shortbus not been to a foreign film in the past 10 years?) And it is unfortunate, as that taboo which Mitchell set out to brake might prove to be the fatal error, attendance wise, in this must see magnificent film. Of course, it would do the film itself a great disservice to simulate what is quite fundamentally its essence. But fucking is never really just fucking, and in when the frigid Sofia finally enters the “back room” of the film’s eponymous club, you get it. You see fucking, true. You also catch wind of promise, nurturing, fear, isolation, devastation, and transcendence – all of this in a swirling, slurping pool of bodies. The impeccable Justin Bond (here proving his legitimacy to me, after never truly being hooked by his Kiki and Herb material) says to Sofia (in the much quoted line) “It’s like the sixties only with less hope.” And that line could completely sum up Shortbus were it not for Mitchell’s signature fairytale styling which renders the film a jubilant concoction of desolation and celebration.

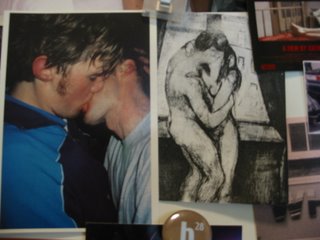

In sequences which made me empathize with the crowd of onlookers who tried to interpret Jack Smith’s Normal Love (for non-regular readers, this is just about the highest compliment I could pay to Mitchell, Smith being a director I hold most dear), I encountered a world which I knew, yet felt foreign, so was it infused with such a fantastic optimism typically deficit in our contemporary, cynical malaise. Sex, or more importantly, human interactions (sex being just one of them) can be endowed with the love which we all too quickly tend to deny ourselves. There’s a photography show of Wolfgang Tillmans on display in Los Angeles right now. Sitting through Shortbus, I could not help but liken both artists’ view of the everyday as quietly utopian. Tillmans’ photograph of two men kissing (which is magnetized to the board in my office) may be read as desperate as a woodblock of Munch’s Kiss, (next to which it is placed). But what if we were to instead to focus on the magnetism of the lovers – the frank and intense want which they display. It is something primal and yet sensitive, never neglecting for a moment the immaculate lighting or similarity of the shirts’ hues. These are real people. They, unlike Munch’s depiction of the kiss, are divorced by the constraints of their own bodies. In many of his versions on this image, Munch fuses his two by removing the line that separates their faces. His is ultimately a warning, where I read Tillmans’ as more of an empathetic invitation – a celebration.

In sequences which made me empathize with the crowd of onlookers who tried to interpret Jack Smith’s Normal Love (for non-regular readers, this is just about the highest compliment I could pay to Mitchell, Smith being a director I hold most dear), I encountered a world which I knew, yet felt foreign, so was it infused with such a fantastic optimism typically deficit in our contemporary, cynical malaise. Sex, or more importantly, human interactions (sex being just one of them) can be endowed with the love which we all too quickly tend to deny ourselves. There’s a photography show of Wolfgang Tillmans on display in Los Angeles right now. Sitting through Shortbus, I could not help but liken both artists’ view of the everyday as quietly utopian. Tillmans’ photograph of two men kissing (which is magnetized to the board in my office) may be read as desperate as a woodblock of Munch’s Kiss, (next to which it is placed). But what if we were to instead to focus on the magnetism of the lovers – the frank and intense want which they display. It is something primal and yet sensitive, never neglecting for a moment the immaculate lighting or similarity of the shirts’ hues. These are real people. They, unlike Munch’s depiction of the kiss, are divorced by the constraints of their own bodies. In many of his versions on this image, Munch fuses his two by removing the line that separates their faces. His is ultimately a warning, where I read Tillmans’ as more of an empathetic invitation – a celebration.

People are sure to find aspects of Shortbus disarming. Mitchell’s film works so magnificently because of its mundanity. In an opening scene, James (Paul Dawson) attempts at autofellatio. Sensational as it may sound (and there is certainly a granted amount time which casts every initial sex act as slightly more scintillating than it truly is as the viewer settles in to the film’s narrative approach) the scene is played out as a quietly domestic one – a way in which this man chooses to come to terms with some form of conflict. All of the actors are so humanized, rather than the typical idolized sex object of our contemporary culture, which is why I would expect some to be startled by the film. Sex, it reminds us, is a product of love. It can be used, like a great many other vestiges of human interaction, as a method of transcendence. It can also be a big Fuck You to all of the conservative powers that be.

People are sure to find aspects of Shortbus disarming. Mitchell’s film works so magnificently because of its mundanity. In an opening scene, James (Paul Dawson) attempts at autofellatio. Sensational as it may sound (and there is certainly a granted amount time which casts every initial sex act as slightly more scintillating than it truly is as the viewer settles in to the film’s narrative approach) the scene is played out as a quietly domestic one – a way in which this man chooses to come to terms with some form of conflict. All of the actors are so humanized, rather than the typical idolized sex object of our contemporary culture, which is why I would expect some to be startled by the film. Sex, it reminds us, is a product of love. It can be used, like a great many other vestiges of human interaction, as a method of transcendence. It can also be a big Fuck You to all of the conservative powers that be.

Shortbus excels in its refusal to submit to a calculated drive. It is aware that it may become sentimental at moments, yet it also wonders how much of a crime that truly is. Do we not need more swelling, earnest sentiment? Do we not need to be reminded of all the potential for connection and love the world just might have in store for us? Do we not need to be reminded of self-empowerment? In a time when so few provocative films allow for optimism, let alone humor, Shortbus emerges like a consoling and intense gale, reassuring us that there is purpose, that the world really does hold both magic and beauty. There is a community for everyone, no matter how estranged. And if there’s anything we need right now, this is it.

Shortbus excels in its refusal to submit to a calculated drive. It is aware that it may become sentimental at moments, yet it also wonders how much of a crime that truly is. Do we not need more swelling, earnest sentiment? Do we not need to be reminded of all the potential for connection and love the world just might have in store for us? Do we not need to be reminded of self-empowerment? In a time when so few provocative films allow for optimism, let alone humor, Shortbus emerges like a consoling and intense gale, reassuring us that there is purpose, that the world really does hold both magic and beauty. There is a community for everyone, no matter how estranged. And if there’s anything we need right now, this is it.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home