So, I've been in New York city the past few days, which accounts for the calm on this Western front, and though I normally wouldn't do this kind of thing, I shall take time here to write about the video work that I saw on my jaunts through the streets of one of the art capitols of the world. Bear with me, or don't read, yet it would seem that filmic "narrative" has infected many works which seem more apt for a non-linear approach.

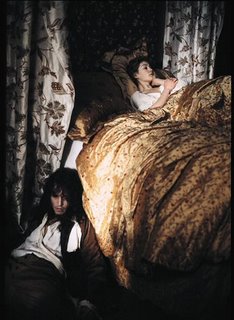

It will comes as no shock that New York is the city of the big boys (and girls), and walking through Chelsea, the only artists allowed to present videos (as video is the hardest to sell, and generally the most costly and demanding - because of its installational qualities - product on the art market today) were, more or less, the big boys. The first video I sat through (well, most of, anyway) was the first video - Proper - directed by Nan Goldin, who fancies herself a video dabbler now. I beg to differ. Goldin, of course, became famous in the Seventies with her slide shows set to the music of the The Velvet Underground or Leonard Cohen. The ever-changing performative "Ballad of Sexual Dependency" was a loose narrative of sexual loss and torment, ripped straight from the life of Goldin's closest friends, even Goldin herself. But you probably already knew that. Goldin's last show at Matthew Marks' Gallery, "Heartbeat" was a creepy, voyeuristic (more so than usual) look at the sex lives of her younger, cuter friends (and in one case, relative), replete with a self-defacing looking-like-hell self-portrait that has already become a sort of sub-category in the artists' ouvre. We have it here, too, along side her first stab at narrative video, Sisters, Saints & Sibyls. The video, which parallels the artist's recently deceased sister to Saint Barbara, sadly, takes most of its inspirations from bad emotional Hallmark docos. Devoid of subtlety, when the narrative asks for a fight, the audio delivers hushed "fuck you"s and "you're a whore"s. When her sister is institutionalized, we hear the slamming of a giant metal door. You get the idea. And try as Goldin might to recapture in video what she so famously depicts in photography (at some points successfully), the construction of the piece at large is so hopelessly artless that one cannot help but feel as though they've stumbled into her sentimental iphoto slideshow.

I beg to differ. Goldin, of course, became famous in the Seventies with her slide shows set to the music of the The Velvet Underground or Leonard Cohen. The ever-changing performative "Ballad of Sexual Dependency" was a loose narrative of sexual loss and torment, ripped straight from the life of Goldin's closest friends, even Goldin herself. But you probably already knew that. Goldin's last show at Matthew Marks' Gallery, "Heartbeat" was a creepy, voyeuristic (more so than usual) look at the sex lives of her younger, cuter friends (and in one case, relative), replete with a self-defacing looking-like-hell self-portrait that has already become a sort of sub-category in the artists' ouvre. We have it here, too, along side her first stab at narrative video, Sisters, Saints & Sibyls. The video, which parallels the artist's recently deceased sister to Saint Barbara, sadly, takes most of its inspirations from bad emotional Hallmark docos. Devoid of subtlety, when the narrative asks for a fight, the audio delivers hushed "fuck you"s and "you're a whore"s. When her sister is institutionalized, we hear the slamming of a giant metal door. You get the idea. And try as Goldin might to recapture in video what she so famously depicts in photography (at some points successfully), the construction of the piece at large is so hopelessly artless that one cannot help but feel as though they've stumbled into her sentimental iphoto slideshow.

Just across the street, at Metro Pictures, artist Tony Oursler, who is proving more and more prolific as the days pass by, offered a collection of video installations, "Thought Forms." Oursler's most recent work (which I have taken to calling "the Dudes," though they all actually have names like Pinky etc.) has found him projecting perversely collaged video, Walt Disney school drop-outs onto knee high porcelain sculptures. The Dudes say absurd things like "pink puddle" or "entertainment...I want to kill you." over and over while smacking their lips, making kissy noises and blinking one of their two off-kilter eyes. I adore the dudes because of their perverted nonchalant entertainment drive. Oursler is recognizing the trend of the art world that yields art which entertains its supporters (yet, of course, labors under one presumption or another as "so much more"), and making a mockery of this desire. This mockery is also proving to be an economic wet dream for Oursler whose "Dudes" are being purchased faster than you can say "pink pink puddle." In his new show, however, Oursler takes the dudes a step (too?) farther.

Oursler's most recent work (which I have taken to calling "the Dudes," though they all actually have names like Pinky etc.) has found him projecting perversely collaged video, Walt Disney school drop-outs onto knee high porcelain sculptures. The Dudes say absurd things like "pink puddle" or "entertainment...I want to kill you." over and over while smacking their lips, making kissy noises and blinking one of their two off-kilter eyes. I adore the dudes because of their perverted nonchalant entertainment drive. Oursler is recognizing the trend of the art world that yields art which entertains its supporters (yet, of course, labors under one presumption or another as "so much more"), and making a mockery of this desire. This mockery is also proving to be an economic wet dream for Oursler whose "Dudes" are being purchased faster than you can say "pink pink puddle." In his new show, however, Oursler takes the dudes a step (too?) farther.  Now, these slightly unsettling portals of easy entertainment, are being assigned a purpose. "Three amorphic materials," the press release informs us, "Mercury, Water, and Dust come together in the exhibition to create an ever-changing dynamic installation. The artist felt that these materials and their symbolic ramifications reflect the present moment in America; a moment of constant flux and lack of solidarity." And though I'm not certain that this is evoked from these sensational works, that humor lent to the earlier Dudes, here proves theatrically rich, as the sculptures now compete with you in size. Their statements are more pointed, more serious, and much of the joie de vivre has been replaced for a more fantastical science fiction read. They are also placed, now, in a setting of projected starscapes and dust clouds. It is a fantastic feat to watch these figures, but after locating this approach to the sardonically entertaining, can Oursler really bring it into the world of earnest criticality. These figures, because of their predecessors, will never shed their entertaining skin. Perhaps most tellingly, upstairs rests a Siamese triplet old-school dude, who, at one point looks at its burdened friends and asks "How did we get here?" How, indeed.

Now, these slightly unsettling portals of easy entertainment, are being assigned a purpose. "Three amorphic materials," the press release informs us, "Mercury, Water, and Dust come together in the exhibition to create an ever-changing dynamic installation. The artist felt that these materials and their symbolic ramifications reflect the present moment in America; a moment of constant flux and lack of solidarity." And though I'm not certain that this is evoked from these sensational works, that humor lent to the earlier Dudes, here proves theatrically rich, as the sculptures now compete with you in size. Their statements are more pointed, more serious, and much of the joie de vivre has been replaced for a more fantastical science fiction read. They are also placed, now, in a setting of projected starscapes and dust clouds. It is a fantastic feat to watch these figures, but after locating this approach to the sardonically entertaining, can Oursler really bring it into the world of earnest criticality. These figures, because of their predecessors, will never shed their entertaining skin. Perhaps most tellingly, upstairs rests a Siamese triplet old-school dude, who, at one point looks at its burdened friends and asks "How did we get here?" How, indeed.

And over at the Whitney, in case you were wondering, the Biennial, this year titled Day For Night was, in fact, as dreadful as people are making it out to be. Relying almost primarily on theatrics (the top floor is a horrifically pandering sight!) it is a sad state for contemporary art. Kenneth Anger, who is graced with a primary location, all but wastes his recognition with a remarkably bad video titled Mouse Heaven. Using tacky techniques, Anger superimposes Mickey Mouse figurines over Mickey Mouse rugs being vacuumed with Mickey Mouse vacuums. Most of his signature cynicism is lost on the piece in its nostalgic and material cheapness. Surrounding the video are screen prints from Invocation of My Demon Brother and narcissistic images of a young and dour Anger which are hung below a set of neon lips that read Hollywood Babylon. All off the ephemera ends up merely confusing itself in a "oh shit, let's make a retrospective!" hurried frenzy.

Kenneth Anger, who is graced with a primary location, all but wastes his recognition with a remarkably bad video titled Mouse Heaven. Using tacky techniques, Anger superimposes Mickey Mouse figurines over Mickey Mouse rugs being vacuumed with Mickey Mouse vacuums. Most of his signature cynicism is lost on the piece in its nostalgic and material cheapness. Surrounding the video are screen prints from Invocation of My Demon Brother and narcissistic images of a young and dour Anger which are hung below a set of neon lips that read Hollywood Babylon. All off the ephemera ends up merely confusing itself in a "oh shit, let's make a retrospective!" hurried frenzy.

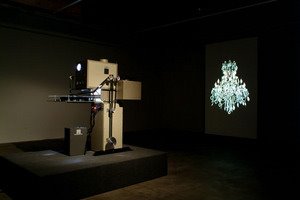

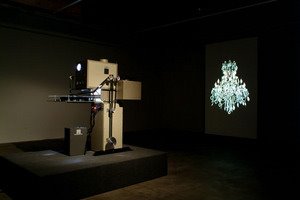

Rodney Graham's sardonic Torqued Chandelier Release was probably the best time-based work in the show (at least, one given the respect of a room, as the Biennial infuriatingly exhibits countless fantastic video and film artists like Lewis Klahr, Michael Snow and Joe Gibbons on monitors placed in the lobby, expecting visitors to stand by the elevator with headphones on for hours on end). Graham's fetishistic installation exposes the inherent yummy-ness(if not modernist masculinity) of 35mm film and, as in the work of Oursler, parodies the Biennial(and thus, in some ways, the art word) itself, likening it to a glistening spinning chandelier. Knowing Graham's work, it is not too much of a stretch to glean this interpretation (His huge 2004 MOCA show was entitled "A Little Thought"). Though it is wonderful to watch the juicy materiality of the chandelier, spinning in a decadent whirl of light and, well... bling-bling.

Rodney Graham's sardonic Torqued Chandelier Release was probably the best time-based work in the show (at least, one given the respect of a room, as the Biennial infuriatingly exhibits countless fantastic video and film artists like Lewis Klahr, Michael Snow and Joe Gibbons on monitors placed in the lobby, expecting visitors to stand by the elevator with headphones on for hours on end). Graham's fetishistic installation exposes the inherent yummy-ness(if not modernist masculinity) of 35mm film and, as in the work of Oursler, parodies the Biennial(and thus, in some ways, the art word) itself, likening it to a glistening spinning chandelier. Knowing Graham's work, it is not too much of a stretch to glean this interpretation (His huge 2004 MOCA show was entitled "A Little Thought"). Though it is wonderful to watch the juicy materiality of the chandelier, spinning in a decadent whirl of light and, well... bling-bling.

And speaking of Bling bling, Francesco Vezzoli's Prada funded Trailer for a Remake of Gore Vidal's Caligula, which premiered at the Venice Biennale in 2004, was a calculated inclusion. Reveling in the pretension and rock-star inaptitude of the art world in general, the hilarious (if not hilariously shallow) Trailer stars, among others, Helen Mirren, Milla Jovavich, Benicio Del Torro, Courtney Love, Karen Black, Michelle Phillips and Gore Vidal, of course. The costumes were designed by none other than Donatella Versace. As a guilty survey of who's who and who's hip, it proves a ridiculously decadent revelry - and isn't that what the original was, before anything else. I applaud current artists for being more comedically parodic, but more than the aforementioned pieces, Trailer caught wind of something decidedly more nasty. Instead of being poignant, doesn't this instead resemble more the baby who soils his own crib rather than rattling at its bars?

There's not much coming to theaters this weekend. There's another Jennifer Aniston dullard whose only perks are its costars. Catherine Keener and Francis McDormand may aid in making Friends With Money almost watchable, though probably not. It seems apt that the first megastar Romantic comedy of the year was titled Failure To Launch.

There's not much coming to theaters this weekend. There's another Jennifer Aniston dullard whose only perks are its costars. Catherine Keener and Francis McDormand may aid in making Friends With Money almost watchable, though probably not. It seems apt that the first megastar Romantic comedy of the year was titled Failure To Launch. Out this week on DVD is a very inexpensive (let's hope this does not mean cheap in production, as well) 5 film, 2 DVD set of films starring Marlene Dietrich. The horribly named Marlene Dietrich: The Glamour Collection arrives via MCA Home Video. Featuring stellar gems like Von Sternberg's Morocco, Blonde Venus (pictured right) and The Devil Is A Woman and lesser non-Von Sternberg films Golden Earrings and The Flame of New Orleans, this collection marks the first time any of these films have arrived on DVD on this side of the Atlantic. This one is a definite purchase best appreciated after reading Underground filmmaker Jack Smith's article on the films of Von Sternberg which can be found here.

Out this week on DVD is a very inexpensive (let's hope this does not mean cheap in production, as well) 5 film, 2 DVD set of films starring Marlene Dietrich. The horribly named Marlene Dietrich: The Glamour Collection arrives via MCA Home Video. Featuring stellar gems like Von Sternberg's Morocco, Blonde Venus (pictured right) and The Devil Is A Woman and lesser non-Von Sternberg films Golden Earrings and The Flame of New Orleans, this collection marks the first time any of these films have arrived on DVD on this side of the Atlantic. This one is a definite purchase best appreciated after reading Underground filmmaker Jack Smith's article on the films of Von Sternberg which can be found here. And in West Hollywood, store owners are going to have to beat off rabid costumers with large sticks as Brokeback Mountain hits store shelves everywhere. Now you too can freeze-frame your way through nude scenes, or you could be the only person actually watching the film in the privacy of your own home.

And in West Hollywood, store owners are going to have to beat off rabid costumers with large sticks as Brokeback Mountain hits store shelves everywhere. Now you too can freeze-frame your way through nude scenes, or you could be the only person actually watching the film in the privacy of your own home. Among other things, a new DVD of the classic (and recently reviewed here) comedy, 9 to 5: The Sexist, Egotistical, Lying Hypocritical Bigot Edition. The DVD boasts a feature commentary with Jane Fonda, Dolly Parton and Lili Tomlin. I wonder how they wrangled that?

Among other things, a new DVD of the classic (and recently reviewed here) comedy, 9 to 5: The Sexist, Egotistical, Lying Hypocritical Bigot Edition. The DVD boasts a feature commentary with Jane Fonda, Dolly Parton and Lili Tomlin. I wonder how they wrangled that?