Almost Blue

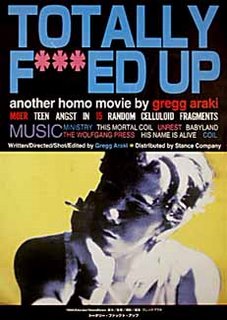

Day Six of Being Boring's Gregg Araki Blogathon.

There's an incredibly artificial animated UFO in the opening minutes of Gregg Araki's Mysterious Skin. It washes the sky with a sumptuous blue hue, illuminating everything beneath it with its radiance. The ovular lights pour over the 8 year old Brian. Gazing up into that light, a maternal arm wrapped around one shoulder, he finds a foreign subject which he may use to displace the very real psychological traumas which he has endured. The UFO, which ultimately proves but metaphorically important, allows him to rewrite his troubled past with a more benign narrative. He was molested, we realize very early on. The alien obsession which would derive from his need to ease the emotional impact of an unrelated incident can be traced right back to that blue wash.

There's an incredibly artificial animated UFO in the opening minutes of Gregg Araki's Mysterious Skin. It washes the sky with a sumptuous blue hue, illuminating everything beneath it with its radiance. The ovular lights pour over the 8 year old Brian. Gazing up into that light, a maternal arm wrapped around one shoulder, he finds a foreign subject which he may use to displace the very real psychological traumas which he has endured. The UFO, which ultimately proves but metaphorically important, allows him to rewrite his troubled past with a more benign narrative. He was molested, we realize very early on. The alien obsession which would derive from his need to ease the emotional impact of an unrelated incident can be traced right back to that blue wash.

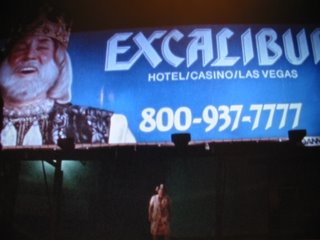

Though color has always been a very integral part of Araki's filmmaking, never before has it reached the methaphoric level at which Mysterious Skin arrives. In prior films, lighting design would typically derive from a brazen need for vibrancy and causticity, but the use of lighting in Mysterious Skin has more to do with the function of memory, how it may inform a scene. Blue, it would turn out, is the true signifier of "the event" in the film. Over every shoulder, blue pours through the windows, from the T.V. Ethereal blue demanding notice in this effervescent world. Even though we're in Kansas (Mysterious Skin marks Araki's first non-L.A. film, it is worthy of mention) every bar, library and bedroom, though hopelessly mundane, carries with it a saturation. As the film progresses, it is as though this saturation is ebbing from our protagonists. That, like that blue light, there is so much walled up within them that it can do nothing but spill out.

Though color has always been a very integral part of Araki's filmmaking, never before has it reached the methaphoric level at which Mysterious Skin arrives. In prior films, lighting design would typically derive from a brazen need for vibrancy and causticity, but the use of lighting in Mysterious Skin has more to do with the function of memory, how it may inform a scene. Blue, it would turn out, is the true signifier of "the event" in the film. Over every shoulder, blue pours through the windows, from the T.V. Ethereal blue demanding notice in this effervescent world. Even though we're in Kansas (Mysterious Skin marks Araki's first non-L.A. film, it is worthy of mention) every bar, library and bedroom, though hopelessly mundane, carries with it a saturation. As the film progresses, it is as though this saturation is ebbing from our protagonists. That, like that blue light, there is so much walled up within them that it can do nothing but spill out.

The film, as a whole, however, is far from perfect. Part of Mysterious Skin's weakness lies in Araki's representation of the rebellious and hostile youths which once proved his calling card. Here it has become a hollow reflex. Casting a delicious crew of recognizable names, none exude the spunk or charisma which made his earlier films so effective. The listless Michelle Trachtenberg being the low point, both Joseph Gordon-Levitt and Brady Corbet lack any inner complexity which has previously been arrived at more fruitfully when Araki casts non-actors to play on their personalities. Excruciatingly affected moments like Gordon-Levitt's "I'm so sick and tired of this sticking buttcrack of a town," come off canned, while those which Gordon-Levitt seems at a loss to understand play off decently, as he has no knowledge as to how his schtick could be of use here. But there's a third act sequence which turns Gordon-Levitt's know-it-all Neil into a meek and understanding human being. He rises to the occasion, fortunately. It is from here on out that the film becomes an impeccable study of grief.

The film, as a whole, however, is far from perfect. Part of Mysterious Skin's weakness lies in Araki's representation of the rebellious and hostile youths which once proved his calling card. Here it has become a hollow reflex. Casting a delicious crew of recognizable names, none exude the spunk or charisma which made his earlier films so effective. The listless Michelle Trachtenberg being the low point, both Joseph Gordon-Levitt and Brady Corbet lack any inner complexity which has previously been arrived at more fruitfully when Araki casts non-actors to play on their personalities. Excruciatingly affected moments like Gordon-Levitt's "I'm so sick and tired of this sticking buttcrack of a town," come off canned, while those which Gordon-Levitt seems at a loss to understand play off decently, as he has no knowledge as to how his schtick could be of use here. But there's a third act sequence which turns Gordon-Levitt's know-it-all Neil into a meek and understanding human being. He rises to the occasion, fortunately. It is from here on out that the film becomes an impeccable study of grief.

When it comes to the adults, Mysterious Skin's fascinatingly daring complexity comes into play. Indie wildcard Bill Sage plays the child molesting coach with such a commendable empathetic air. Unlike most films which represent such figures as mere sexual predators, Mysterious Skin meditates on the fact that the coach is a man with desires. He does not make a flesh eating monster out of him, but merely renders him in all of his wiley, yet neurotically covert sexuality. It is a performance which rivals Dylan Baker's pedophile in Solondz's Happiness in its willfulness to surpass judgment and play him as a man, not merely a villain. The camera eerily views him as any child would. In most of the shots, his face fills the frame - an approach which holds both physical and metaphorical significance.

When it comes to the adults, Mysterious Skin's fascinatingly daring complexity comes into play. Indie wildcard Bill Sage plays the child molesting coach with such a commendable empathetic air. Unlike most films which represent such figures as mere sexual predators, Mysterious Skin meditates on the fact that the coach is a man with desires. He does not make a flesh eating monster out of him, but merely renders him in all of his wiley, yet neurotically covert sexuality. It is a performance which rivals Dylan Baker's pedophile in Solondz's Happiness in its willfulness to surpass judgment and play him as a man, not merely a villain. The camera eerily views him as any child would. In most of the shots, his face fills the frame - an approach which holds both physical and metaphorical significance.

Elizabeth Shue's performance as Neil's slutty mother is a quietly complicated one. On first viewing I wrote her off as doing her best Jennifer Jason Leigh, yet her intricate relationship as the immature mother of the too-mature Neil is fascinating to behold. They stare past the television, in one scene, more veterans than family members. They trade off the same cigarette as Shue boasts potential dates with men who frequent her lane at the local grocery store. When he leaves for New York, you actually feel the resentment mixed with sadness which builds in her eyes.

Ultimately, the flaws add up. I cannot consider it Araki's best work. Yet Mysterious Skin is an interesting development in his ouvre. The need to be fashionable which marred Splendor is gone, and you get the sense that Araki made this film because he really wanted to. You can feel that in it, certainly. It is a very transcendent film in many ways - the ending serving as one of the films greatest attributes. Most importantly, it proves Araki's certainty as a director; that he's matured, but in many cases, stuck with his initial impulses. It's a lot more like his earlier work than the frenetic, frenzied LA scenes for which he would most become famous (or if not, at least dubious) and he's all the better for it.

Ultimately, the flaws add up. I cannot consider it Araki's best work. Yet Mysterious Skin is an interesting development in his ouvre. The need to be fashionable which marred Splendor is gone, and you get the sense that Araki made this film because he really wanted to. You can feel that in it, certainly. It is a very transcendent film in many ways - the ending serving as one of the films greatest attributes. Most importantly, it proves Araki's certainty as a director; that he's matured, but in many cases, stuck with his initial impulses. It's a lot more like his earlier work than the frenetic, frenzied LA scenes for which he would most become famous (or if not, at least dubious) and he's all the better for it.