Dark Shadows

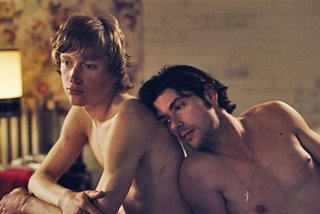

Above, Ozon(L) and Melville Poupaud on the set of Le Temps Qui Reste.

Above, Ozon(L) and Melville Poupaud on the set of Le Temps Qui Reste.

There's a lot to be said about the cinema of Francois Ozon. His seemingly bipolar array of tastes, from viscous to camp to (almost)neorealist to back again have caused an enticing and varied expectation which arrives with each new film. 8 Women, perhaps his most commercially successful film, offered an unparalleled extreme in postmodern melodrama, which, a few years later, functioned in direct contrast to the starkly realistic film structured around a set theorem: an ill-fated relationship told in in five reverse order sequences: 5x2. Because of his earlier, more tempestuous works(Sitcom, Criminal Lovers and the Fassbinder penned Water Drops on Burning Rocks), he was considered France's enfant terrible. Even his more mundane works avoid pure verite by their almost subconscious acknowledgement of the director's Camp tactics and melodramatic tendencies.

That being said, Ozon's recent works have proven, at least to this eye, lackluster at best. Though commercially successful, The Swimming Pool proved too clever for its own good, and most of the director's signature spunk was absent from the aforementioned 5x2. That his forthcoming offering, Le Temps Qui Reste (literally The Time that Remains but bewilderingly mistranslated as Time to Leave) recommences a dance with death previously meditated on in Ozon's magnificent Sous le Sable (Under The Sand) is a step in the right direction. Where Sable starred the statuesque Charlotte Rampling, in a slightly autobiographic act, Le Temps Qui Reste focuses on a startlingly beautiful and successful homosexual, not too far from Ozon's own age. Portrayed by Melville Poupaud, Romain is diagnosed with terminal cancer. The film follows the brief remainder of Romain's life, how he chooses to cope with his disease and in whom to look for comfort.

That being said, Ozon's recent works have proven, at least to this eye, lackluster at best. Though commercially successful, The Swimming Pool proved too clever for its own good, and most of the director's signature spunk was absent from the aforementioned 5x2. That his forthcoming offering, Le Temps Qui Reste (literally The Time that Remains but bewilderingly mistranslated as Time to Leave) recommences a dance with death previously meditated on in Ozon's magnificent Sous le Sable (Under The Sand) is a step in the right direction. Where Sable starred the statuesque Charlotte Rampling, in a slightly autobiographic act, Le Temps Qui Reste focuses on a startlingly beautiful and successful homosexual, not too far from Ozon's own age. Portrayed by Melville Poupaud, Romain is diagnosed with terminal cancer. The film follows the brief remainder of Romain's life, how he chooses to cope with his disease and in whom to look for comfort.

Yet Roman is not your typical, sentimental subject. He's quite a bastard, in truth. His vanity and stubbornness prevent him from connecting to his immediate family and young lover. He confides in his grandmother (cine diety Jeanne Moreau) because, "we are both close to death." And Ozon is at no loss to return the favor, Romain's suffering is obviously self-inflicted - of this we are perpetually reminded. He clings to the glorified memories of a simpler childhood from which he incapable of maturing.

Yet Roman is not your typical, sentimental subject. He's quite a bastard, in truth. His vanity and stubbornness prevent him from connecting to his immediate family and young lover. He confides in his grandmother (cine diety Jeanne Moreau) because, "we are both close to death." And Ozon is at no loss to return the favor, Romain's suffering is obviously self-inflicted - of this we are perpetually reminded. He clings to the glorified memories of a simpler childhood from which he incapable of maturing.

And like the husband's reappearance in Sous Le Sable, this idealized childhood takes on great metaphoric import. Images of the young, rambunctious Romain haunt the screen - even before we are treated to images of the adult Romain. And memory, too, functions as a ghost, reemerging at the film's more somber moments to complicate the way in which Romain approaches (or denies) the fleeting opportunities for connection with others. You begin, quite quickly, to understand that no moment which remains of Romain's short life will endow the importance as those which have already passed. The camera lingers mere inches from its present day subjects (blues and greys) and seldom allows for the distance (freedom) of these nostalgic shots - all golden glowing and spaciously choreographed. The most glorious moment of the film, an amorous shot of Romain and Sascha, windblown and smiling against a clear blue sky, is immediately preceeded by a haunting journey into the lowest fuck den of a Parisian gay bar - more a Dante depth than an architectural one. Memory is never what actually happened but instead glorified in how we recall it - and darker times only brighten those memories held most dear.

Though there are points when the film becomes a tad too maudlin for its own good(which is aided by a soaring classical score which I both adored and am tremendously suspect of), by and large, it is genuine and controlled. The tendency which Ozon has to mingle the more typical Genre moments (saying goodbye to a family member) with the more privatized ones (vomiting up a lunch which was painstakingly consumed) is ultimately dynamic, and yet, one wonders how much more potent of a tale it would have been to infuse just a touch more melodrama to the proceedings. It's there already but in this achingly morose tale, it would seem either a little less or a little more was necessary to truly make it blossom(and here I am certainly not musing on the level of melodrama which met 8 Women).

Though there are points when the film becomes a tad too maudlin for its own good(which is aided by a soaring classical score which I both adored and am tremendously suspect of), by and large, it is genuine and controlled. The tendency which Ozon has to mingle the more typical Genre moments (saying goodbye to a family member) with the more privatized ones (vomiting up a lunch which was painstakingly consumed) is ultimately dynamic, and yet, one wonders how much more potent of a tale it would have been to infuse just a touch more melodrama to the proceedings. It's there already but in this achingly morose tale, it would seem either a little less or a little more was necessary to truly make it blossom(and here I am certainly not musing on the level of melodrama which met 8 Women).

Cinematically speaking, Le Temps Qui Reste is both a step forward and back for Ozon. Significantly more mature than his previous works, it is the youthful beastly malevolence which leaves a shadow here, one which I as a viewer miss greatly. In past films, Ozon's presumptuousness brought something to the table. It was endeering. Embracing a more A grade cinema aesthetic, a grain which his earlier films more worked against, Ozon has accomplished a more digestible work of cinema. That the provocation usually ascribed to the filmmaker is absent might by excused by the subject, yet there is an air of daring that seems to be on the back burner for this one. Don't get me wrong, Le Temps Qui Reste is a good film. It is also undeniably a film by Francois Ozon. Yet it is neither a great film, nor is it stand-alone within the canon of this auteur. But I would lose sleep if I did not highly recommend it.

1 Comments:

I thought Swimming Pool was a lot more commercially successful than 8 femmes.

Post a Comment

<< Home