So I've not really been as negligent as it may appear. For the past couple months I've been culling together a selection of writings which I'll self-publish earlier this year (stay tuned) called Bad: Critical Musings on Film's Faultier Gems - hence the lack of recent posts. But it's not that I haven't been thinking. Over the past week, during a moment of great fiscal famine, I resigned to my apartment, armed with season one of Melrose Place to fill the time which I could not allot to more socially driven exercises.

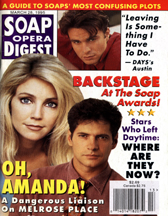

Now we're talking 24 hours of entertainment (excluding the special features, of course) packed onto 8 discs. Though I'm still three eps shy of completion, it's already got my mind churning on a far more complicated structural phenomenon which, not only assured Melrose Place its steady audience, but is one of the greater determining factors of filmic/televisual viewing. From soulless Hollywood pictures to obscure foreign cinema, serial use of the star is something which, though analyzed indepth as it pertains to individual studies (biography, development, genre tropes), is not something frequently ruminated upon in contemporary film studies. Why, for instance, do I shriek with glee when Amanda (Heather Locklear) finally assumes her role as Queen Bitch and proclaim "Oh, Sammy Jo"?

Has Melrose Place ever laid claim to her bitch heritage, explicitly? Has there been a direct meta moment in which even the word "Dynasty" or title "Sammy Jo" uttered? No. And yet, we bring to these actors an understanding of their role within a larger narrative framework. Of course, a great joy arrives when an actor place against type - think Kristin Davis' transformation from Melrose maven to Sex and the City's sheltered Charlotte, or, more decorously, Barbara Stanwyck's fluid shifting from Double Indemnity to Christmas in Connecticut - but, more often than not, a great determinant to Pop success lies in its conduit's familiarity. I know Heather Locklear. I know she's a bitch - at least, that is how I understand her from her previous roles. When she appears in Melrose Place as Alison's chummy work partner, we bide our time, safe in knowing that soon the dragon shall be unleashed. It's easy, but positively rewarding.

Has Melrose Place ever laid claim to her bitch heritage, explicitly? Has there been a direct meta moment in which even the word "Dynasty" or title "Sammy Jo" uttered? No. And yet, we bring to these actors an understanding of their role within a larger narrative framework. Of course, a great joy arrives when an actor place against type - think Kristin Davis' transformation from Melrose maven to Sex and the City's sheltered Charlotte, or, more decorously, Barbara Stanwyck's fluid shifting from Double Indemnity to Christmas in Connecticut - but, more often than not, a great determinant to Pop success lies in its conduit's familiarity. I know Heather Locklear. I know she's a bitch - at least, that is how I understand her from her previous roles. When she appears in Melrose Place as Alison's chummy work partner, we bide our time, safe in knowing that soon the dragon shall be unleashed. It's easy, but positively rewarding.

That authoritative understanding of character (how I know Amanda before she shows her true colors) is key to the way we approach any given work - be it art, film or literature. Preconceptions are always great determining factors in how and what we choose to consume. It's the drive which makes my mother (and perhaps, secretly, myself) eager to see Words and Music even though the plot matters nil to the fact that it stars romantic regulars Hugh Grant and Drew Barrymore. But there is a more affirmative, even authoritative gesture in serial character recognition.

It's one which German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder understood fabulously. Branching out in film from theater, he brought along his troupe and seldom made a film without an assortment from his wealth of "regulars." Each actor typically imbued a certain genre type: Margit Carstensen was his neurotic spinster; Briggite Mira his elder, put-upon worker; Hanna Shygulla, his tabula rasa en route to corruption; Irm Hermann, alien. It was a structure he would coyly exploit. Following her sincere performances in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul and Mother Kusters Goes to Heaven, with Chinese Roulette, Briggite Mira is cast again as a woman of labor, but a decidedly more viscous one who takes sips from the liquor cabinet and longs for the death of her employers. Carstensen, made famous by her appearance as the title character of The Bitter Tears of Petra Von Kant, appears in Fassbinder's critique of bourgeois politiciality, The Third Generation, as a character smugly named Petra. And yes, when Carstensen hits the screen, however dramatic or calculating the film, I indiscriminately shriek "oh Margit!"

As I read them, Fassbinder's films become an elongated, schizophrenic soap opera. It's apt that the pinnacle of his artistic production was Berlin Alexanderplatz, a 13 1/2 hour, fourteen episode television miniseries. Unleashing his plethoric crew of actors on this mammoth production, regulars in typical roles earned the time for the Soapy episodic development only hinted at in their prior, internarrative character plays. Your familiarity initially informs them, but they are allowed a development alienated by feature structure. Fassbinder, a famous Sirk enthusiast, would have culled (and expanded) this approach from Sirk's use of actors like Jane Wyman and Rock Hudson, who would be perennially recast as the same figure - however differing their settings and situations. Fassbinder celebrates and subverts this in his meta-recognition, but it is the viewer who must ultimately make the associative links which create his films as one epic, genre-weaving saga.

It's a wide chasm, but a wholly similar one which instills the giddy recognition at play in Melrose Place. Here, we are, of course, given full and linear character development - though it is not one without its exterior influences. In discussing my marathon with friends, people were endlessly referring to Andrew Shue, not by his name, but as "Elizabeth Shue's brother." Daphne Zuniga to was cooed with people's prior affectations to her. It's no new claim to understand the appeal of Soap actors (or just actors in general) as viewer's familiars or "friends." Finding comfort in the recognizable is common. I just find the amount of meta-narrative associations rather fascinating when they come into play - particularly as it pertains to Genre - and the Soap is nothing more than a logical evolution of the Women's picture.

>Fassbinder's films, however searing, were ultimately Women's films. Though it would be totally daft to claim this a phenomenon exclusive to the Ladies' movies. Think of all of the outside sources at play within Action cinema - from Stallone to Die Hard to Crank and back to Jean Claude Van Damme. I'm constantly claiming, to much initial consternation, that there is little difference between a Women's Film and the most sensational Shoot-Em-Up fare. It is, in part, evidenced by this inter-role play. Part confiding, part reassuring, these are figures who have not only marked a prior moment in our lives (and thus function as a sort of nostalgic aphrodisiac) but are dependable to reappear and remind us of their consistency, so that we may shriek once more, "Oh, Sammy Jo!"

Hi

ReplyDeleteVery nice and intrestingss story.