Day one of Being Boring's Araki Blogathon.

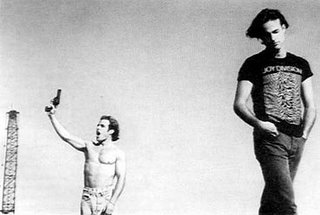

What proved to be the first proper theatrical exposure to the cinema of Gregg Araki, The Living End, heralded the phrase "Fuck the World." Tagging a cement wall with a heavy industrial KMFDM track on his headphones, a leather jacket clad Luke, the id in our pair of protagonists, dances back in his Jesus & Mary Chain sleeveless and twirls about to the tune. A very polluted and industrial Los Angeles provides his backdrop. Jon, very much our superego, drives on a crowded LA freeway listening to something industrial, though decidedly more faggy. He is understandably shattered after receiving his first, positive HIV test from an dispassionate doctor. Both are HIV positive, we eventually learn. That the two will eventually meet is rather apparent. That they have much to offer one another - even more so.

What proved to be the first proper theatrical exposure to the cinema of Gregg Araki, The Living End, heralded the phrase "Fuck the World." Tagging a cement wall with a heavy industrial KMFDM track on his headphones, a leather jacket clad Luke, the id in our pair of protagonists, dances back in his Jesus & Mary Chain sleeveless and twirls about to the tune. A very polluted and industrial Los Angeles provides his backdrop. Jon, very much our superego, drives on a crowded LA freeway listening to something industrial, though decidedly more faggy. He is understandably shattered after receiving his first, positive HIV test from an dispassionate doctor. Both are HIV positive, we eventually learn. That the two will eventually meet is rather apparent. That they have much to offer one another - even more so.

Taking its place in the "lovers on the lam" genre, a comparison to films like Bonnie and Clyde is not undeserved. Only, that reviled society of sheriffs and bank tellers which the latter couple opposed, here, in a rather deft move of contemporary poignancy, manifest internally. That is, rather than making the enemy that society which Luke so readily blames, it is located within himself, in the blood. In Luke's case, it debilitates him with the fear of his physical condition. Tough and gruff, Luke counters every obstacle which stands before him with a bombastic rebelliousness desperately ebbing with insecurity. Jon, ever the pragmatist, is philosophically crippled, though he sloughs it off claiming, "I've just got to lay off the Joy Division records."

It's comments like these that bring most of Araki's detractors to find his films shallow or unoriginal. Cataloging cultural referents is a huge part of Araki's ouvre, though not in any detrimental way. His are regional period pieces, succinctly embodying the film's era as much as it's southern California terrain. Entering Jon's apartment, posters adorn the walls for Goddard's Made in the USA and The Films of Andy Warhol. Depeche Mode and New Order CD's litter his floor while messages on his answering machine talk of the Revolting Cocks, Nitzer Ebb and performance art. The lesbians who try to shoot Luke at the film's opening (one of them, factory maven Mary Woronov, playing a delicious parody of herself; the other, 80's performance artist Johanna Went) only have tapes by K.D. Lang. Am Pm, Ralph's, 7/11, Circus Liquor set the scene. All of this adding up to a frenzied summation of urban pastiche - and here it is far more damning one than those hip locales of Araki's later fare.

It's comments like these that bring most of Araki's detractors to find his films shallow or unoriginal. Cataloging cultural referents is a huge part of Araki's ouvre, though not in any detrimental way. His are regional period pieces, succinctly embodying the film's era as much as it's southern California terrain. Entering Jon's apartment, posters adorn the walls for Goddard's Made in the USA and The Films of Andy Warhol. Depeche Mode and New Order CD's litter his floor while messages on his answering machine talk of the Revolting Cocks, Nitzer Ebb and performance art. The lesbians who try to shoot Luke at the film's opening (one of them, factory maven Mary Woronov, playing a delicious parody of herself; the other, 80's performance artist Johanna Went) only have tapes by K.D. Lang. Am Pm, Ralph's, 7/11, Circus Liquor set the scene. All of this adding up to a frenzied summation of urban pastiche - and here it is far more damning one than those hip locales of Araki's later fare.

Here, the neon lights which line the vacant parking lots of the Ralph's cast a morbid hue over the errant souls which inhabit them. The signs replace the moon. When it comes to Araki's use of billboards and (to appropriately use a Siouxsie song title) mad eyed screamers, however, the alienating critical scrutiny of Araki's cinema comes into full form. Never do our protagonists seem so lost as when they appear beside the countless crazies that flow in and out of the most unlikely of places(as is true of the real Los Angeles). Two S/M couples pass our protagonists at random moments, leading their submissive by a leash. Their appearance assures Luke's comment that the world is a random fucked up place.

What I had not been prepared for, was the film's emotional complexity. True, later Araki works assumed the guise of the MTV video(where it became an act of subversion, but more on that later), The Living End shines with a neo-realist exploration of character. The characters are, in many ways, more generalized tropes tropes of queer cinema (see Thomas Waugh's "The Third Body"), but my remembrance of the film had fixed the characters as vaguely developed reactionaries, when in fact, upon more recent inspection, they are very vulnerable and emotionally faceted. Jon, with his Smiths records and Derek Jarman readers, is your more typical depressive intellectual (and assuredly more autobiographical, particularly when considering his ties to cinema). Luke, on the other hand, proves a fantastic figure of trembling denial, hiding his feelings with a pistol, glossing over his trepidation with boisterous retorts and violence. And this, it turns out, robs him of all conviction. In the end, it his is dishonest affronts that foil his selfish plans for denouement. And still, as far from the trail as Luke has taken him, Jon realizes that it has not all been for naught. They are brethren, of a sort. Blood brothers. But lovers, too. Through this voyage, not only has Jon come to love Luke(in some way, at least), but he realizes what Luke does not. It is through an understanding of both his (Jon/Superego) and Luke's (id) approaches to life that will give them the wherewithal to rationally comprehend what they've been dealt. Luke lead him to distract him from a devastating blow, now it is Jon's turn to do the leading.

What I had not been prepared for, was the film's emotional complexity. True, later Araki works assumed the guise of the MTV video(where it became an act of subversion, but more on that later), The Living End shines with a neo-realist exploration of character. The characters are, in many ways, more generalized tropes tropes of queer cinema (see Thomas Waugh's "The Third Body"), but my remembrance of the film had fixed the characters as vaguely developed reactionaries, when in fact, upon more recent inspection, they are very vulnerable and emotionally faceted. Jon, with his Smiths records and Derek Jarman readers, is your more typical depressive intellectual (and assuredly more autobiographical, particularly when considering his ties to cinema). Luke, on the other hand, proves a fantastic figure of trembling denial, hiding his feelings with a pistol, glossing over his trepidation with boisterous retorts and violence. And this, it turns out, robs him of all conviction. In the end, it his is dishonest affronts that foil his selfish plans for denouement. And still, as far from the trail as Luke has taken him, Jon realizes that it has not all been for naught. They are brethren, of a sort. Blood brothers. But lovers, too. Through this voyage, not only has Jon come to love Luke(in some way, at least), but he realizes what Luke does not. It is through an understanding of both his (Jon/Superego) and Luke's (id) approaches to life that will give them the wherewithal to rationally comprehend what they've been dealt. Luke lead him to distract him from a devastating blow, now it is Jon's turn to do the leading.

No comments:

Post a Comment